NOBODY'S (*Everybody's!) FASHION WEEK STREETWARE SAVED ITEM DESIGN AS COMMON GOOD WAREHOUSE

ADDRESS JOURNAL

→ Performative Processes

→ New Mentorship

→ Archivist-Creators

→ Alternative Fashion Media

→ Future Fashion Education

→ Mended Scars

→ Second Life

→ Fast Fashion Disruption

BLOOMSBURY FASHION CENTRAL

SEARCHING FOR THE NEW LUXURY

Out of the Shadows: Are we there yet?, 2021 →

Embedded Research, in progress, 2021 →

Speculative Citizen Design, 2020/21

A Magazine Reader and the rise of the Unglossies, 2020

Fashion from the Shadows Series, 2017-2019

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 13.01.2019

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 14.08.2018

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 25.02.2018

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 14.11.2017

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 12.09.2017

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 20.07.2017

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 26.06.2017

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 24.05.2017

Designer Biographies, 2018 →

Authentic Fashion Products!, 2018

ADDRESS Journal for Fashion Criticism, 20.07.2017 [*]

Sweater by maker and researcher Bridget Harvey for the Climate March (2015)

Sweater by maker and researcher Bridget Harvey for the Climate March (2015)

ETHOS

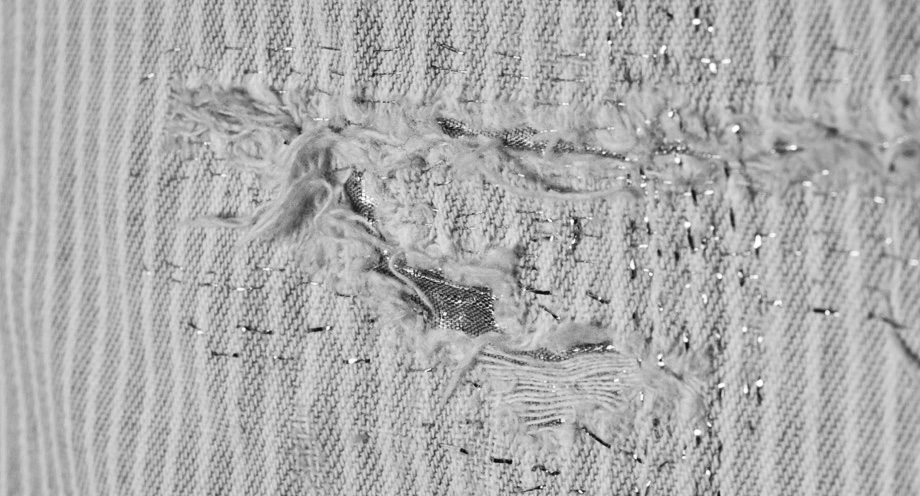

Once a regular chore, mending clothes has become a lost practice as replacements are cheaper, free time scarce and domestic skills forgotten in favor of digital technologies. As a result, mended scars are rarely found in garments anymore.

Without a hint of nostalgia, new projects aiming to revive these lost traditions of mending adapt contemporary aesthetics to motivate fashion enthusiasts to care for their clothes. This new mending movement is not purely born out of financial necessity or environmental concerns. Instead, the proponents of this tradition strongly believe that the act of repair does not only serve to bring a garment back to its original state, but rather adds to its value and demarcates a visible episode in its history by inscribing traces of use and care. It is as much a reaction against disposable fashion as it is a poetic expression of beauty in the imperfect.

Mended scars tell a story beyond the original design of the piece and transform garments from mass-produced goods to individual objects with visible histories. The scars are a reminder of the human work that stands behind anonymous objects and help to create a personal connection with the mender as well as with all the other people that helped the garment come alive through production and prior use. As well as facilitating a connection with the past, mending creates a space for focused time and attention.

Wearing imperfect, mended garments, is a way to show pride in the human hand. While perfect pieces seldomly elicit thoughts about their making, it is the small deviations that act as reminders of their humble origins. Not only do mended pieces archive the passage of time, they highlight something very personal about the wearer: loyalty beyond superficial standards of value and beauty.

‘The Catalog of holes’ (2010) by textile artist Celia Pym

‘The Catalog of holes’ (2010) by textile artist Celia Pym

Whereas new clothes are promises of new identities and new beginnings, those with mended scars represent overcoming of the past. A favourite sweater loaded with personal memories is not easily replaced. The hole accidentally torn into it and grieved for does not devalue the garment as a whole with all its emotive associations. It represents an opportunity to add to the narrative potential of the piece and to heighten its value by strengthening its bond with the wearer, who puts in the effort for saving it. Mended clothes with their extended lifetime take on a humble, yet central role in a wardrobe, slowly becoming its oldest inhabitants, more precious with each intervention.

Mended clothes are worn as badges of honour, paying tribute to other people’s work and showing respect for their craft. They remind the onlooker of the humanity of the wearer, breaking down barriers between people that fashion often creates by serving as an armour of constructed public image. Instead of being a social divider, mended clothes communicate vulnerability and approachability. Trust, mutual recognition and honesty replace admiration, power and insecurity. Mending unveils the construction of the piece and its failure to withstand the test of time, mirroring the complexity of human nature that is impossible to reduce to seemingly perfect appearances.

KEY TACTICS

Mending, Repair Kits, Reframing, Interventions, Workshops, Visual Branding, Storytelling

CONTEXT

Before high-scale industrial production, when home-sewing was still the norm, the effort that went into making clothes was not an abstract notion but a ritual embedded in each household. Low availability and high price of clothing, as well as prohibitive fabric costs before the introduction of synthetic fibers, all added to the perceived value. Being considered an investment, great effort was put into getting the longest use out of a piece that often had to serve multiple generations.

Regular wardrobe updates were only for the wealthy and thus, sensible, durable clothes were preferred. Festive and delicate outfits remained exceptional, as they were easily soiled or otherwise deteriorated. In the event of rips and tears, mending was the remedy, ranging from quick repairs to elaborate decorative techniques to mask mishaps.

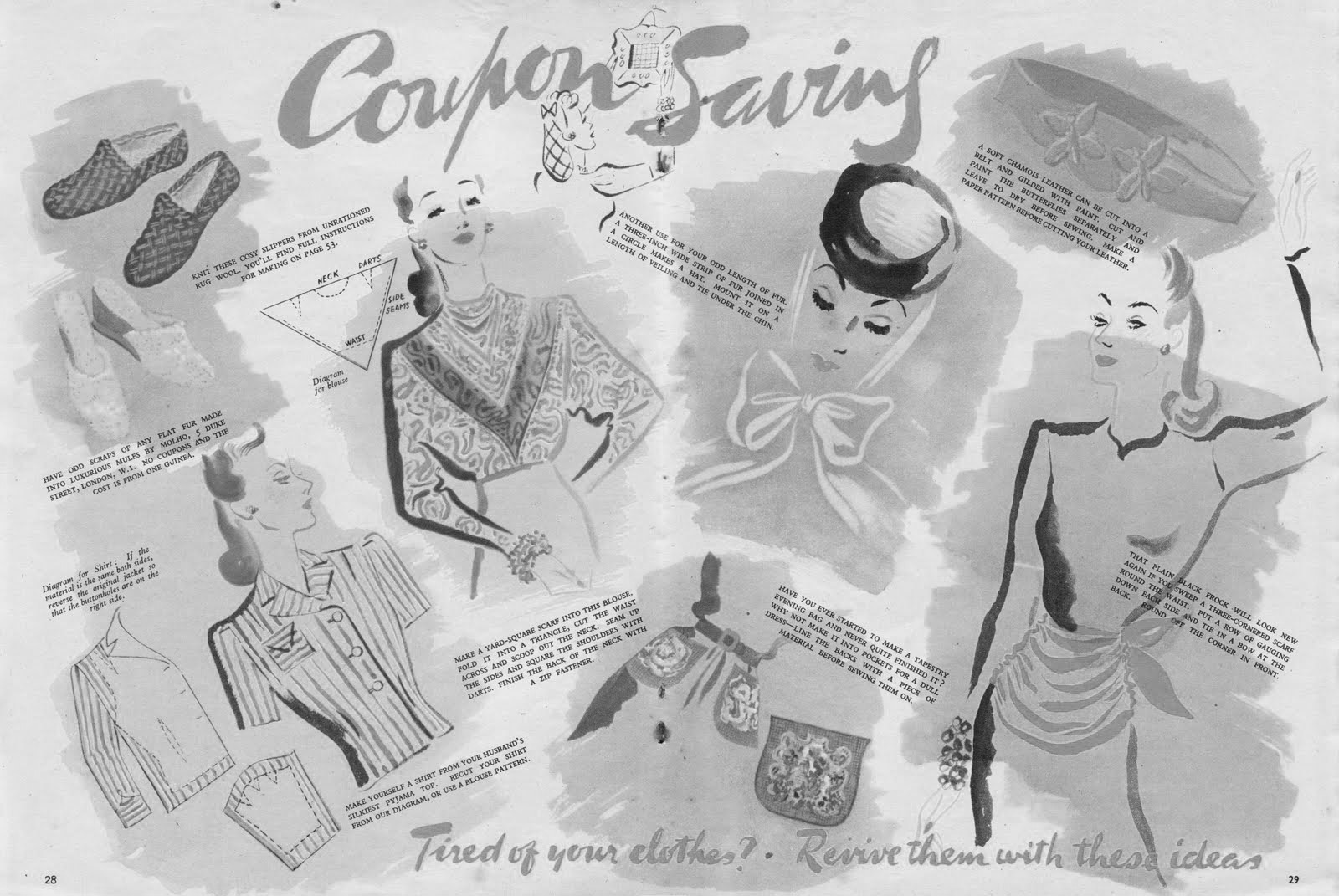

When wartime prevented new clothes from being made for civilians as producers’ capacity was filled with the production of uniforms and parachutes, and fabrics were rationed, the art of mending was shared through print publications. The British Ministry of Information distributed ‘Make Do and Mend’ pamphlets during World War II and magazines at the time contributed to the dissemination of information about mending. When worn and mended clothes became the norm, skill and ingenuity became important in order to differentiate rags and appropriate attire.

Boro panel (circa 1920)

Boro panel (circa 1920)

In Japan, the mending technique boro, using scraps of indigo-dyed discarded fabrics to repair old clothes by repeatedly superposing them, was lost during the 1950s due to rising living standards and coming to terms with the past after World War II. The pieces, mainly made by peasants, were associated with poverty and lower classes. However, recently the technique has gained in cultural capital through exhibitions as an example of wabi-sabi and from being re-appropriated by fashion designers.

While the economic recession of 2008 partly contributed to a renewed interest in making clothes last longer, the movement relates more closely to minimalist tendencies as well as DIY culture. These lifestyle philosophies demand a renewed awareness of consumption habits and their impact on the world, as well as self-sufficiency and a spiritual quest for honouring what one already has. Democratised abundance, the dream of perpetual growth, improvement and outsourcing for individual advancement have led to the resurfacing of Renaissance ideals of multiple skillsets and a shift in what it means to lead an accomplished life. Digitalisation and a loss of practical skills have prompted the desire to reconnect with the material world along with a longing for slowness and consistency. Among designers and brands, the new mending is a way to deal with the reality of overproduction and consumption while still offering an outlet for creative expression, justifying the relevance of their clothes in a fast-paced market.

Iranian Carpet mended with needle felting (2012) Heleen Klopper

Iranian Carpet mended with needle felting (2012) Heleen Klopper

During a time of widespread guilt, blaming and activism, mended scars also represent an expression of care and wanting to make things right at every scale. When world issues and unpredictable events seem overwhelming, it is the small things that are being fixed again. These simple actions give the menders new confidence in their abilities and a positive outlook towards a future that holds together, scarred yet beautiful. The new mending movement is thus not a regression into the past or a longing for simpler times, but rather an accurate expression of the present. It combines individual storytelling, personalization, environmentalism, awareness of working conditions in the global industry with the desire for compassion and strength in the face of adversity as a reaction to failures in the industry and global politics alike.

CASE STUDIES

– Two fashion activists from the Dutch collective Painted Series took it upon themselves to translate the Japanese method of Kintsugi, the repair of broken porcelain with gold filling the cracks into its fashion equivalent. The Golden Joinery hosts collaborative workshops run by Saskia van Drimmelen and Margreet Sweerts where participants bring their own torn clothes and learn to use golden thread and newly learnt techniques to mend them. The ornament is celebrated and notions of value, flaw and novelty are discussed. Moreover, the collective developed the Golden Joinery Game to widen their audience and spread the movement even without their presence. Each purchase of the game kit helps to support the Clean Clothes Campaign. The aim of the project is to question the monopoly of fashion labels as well as to explore new ways of doing fashion.

– Heleen Klopper’s Woolfiller proposes a simple solution for mending holes using coloured wool and the technique of needle felting. Similarly to the Golden Joinery, she hosts workshops for filling sessions and sells toolkits for repair beyond the collaborative meetups. With low effort, garments are darned and decorated, receiving a distinctive look. Flaws are turned into ornaments and hidden in plain sight. The simplicity of the Woolfiller method and its distinct appearance offer a contemporary take on mending that has the potential to be adopted by those reluctant to take up slower mending techniques.A continuation of this project is being developed under the name Made to Mend, which is a material designed to be mended and is accompanied by a clothing line.

Vintage cardigan repaired with vintage wool by Tom of Holland

Vintage cardigan repaired with vintage wool by Tom of Holland

– Former magazine editor Kate Sekules founded Visible Mending after a success with the personal closet trading platform Refashioner. It is a growing online platform created to make mending and caring for old clothes more attractive, uniting smaller independent mending projects under one roof. It showcases the works of textile artists Tom of Holland (who is also helping others at the Brighton Repair Café and has coined the term Visible Mending), Celia Pym, Miriam Dym of the Logo Removal Service and many others. The featured projects represent a wide range of approaches to mending, from basic repair and the revival of ancient techniques (such as by royal embroidery company Hand & Lock) to more conceptual and artistic projects. The project aims to combat overshopping and to generate a culture of respect for the makers of fashion.

– Swedish denim brand Nudie Jeans has placed repairs at the centre of its strategy, along with other environmentally conscious practices. The brand’s Repair Shops, where sewing machines are visible in the stores instead of hidden in workshops, offer mending services for broken pieces. This setup serves to create awareness of ways to extend the lifetime of clothes and building brand loyalty beyond consumption. In addition to repair services offered free of charge, Nudie Jeans resells second hand products brought back by customers, recycles pieces that have reached the end of their use and strives for sustainable and transparent production. Brands that embrace repair before buying and provide the necessary services help to establish more sustainable consumption patterns and reach people who would not usually mend clothes themselves. Instead of opposing it entirely, they present alternatives within the system whilst contributing to make slow changes that shape new ways of thinking.

– Another brand that has been promoting ethical and sustainable practices in fashion is Patagonia. With its Worn Wear initiative, it encourages customers to take care of worn clothes by proposing an Expedition Sewing Kit, extensive product care guides and step-by-step Quick Fix Guides that are also featured in the Android app iFixit. These DIY resources are complemented by free mending services. Patagonia’s Repair Truck, equipped with a sewing workshop goes on tours across the USA to provide free clothing repairs and hold workshops to show customers how to mend garments themselves. The truck stops at sustainability and outdoor events and college campuses to get closer to its community while making use of social media to spread the message. The brand does not stop producing new clothes and is aware of the seeming contradiction, but it uses its position in retail to shift consumers’ attitudes towards their clothes. This approach creates a bridge between smaller mending projects that have less reach and retail customers who form the majority. Collaborative workshops are a recurring element in many mending projects, presenting the task not as a chore but as a social activity over which personal stories and thoughts on sustainability can be shared. The proximity and common task of the participants creates an intimate atmosphere. This adds to the positive memories inscribed into the mended pieces and turns mending into a collective movement instead of a solitary task.

– The Renewal Workshop is an American company that dedicates itself to extending the lifetime of unsellable apparel inventory. The items, used and unused, are sorted, cleaned and repaired. They then enter their next existence away from storage rooms and landfills. The aim of the workshop is to recover value, reduce waste and make people appreciate what would otherwise be lost. Due to the acquisition method, the history of the garments remains unknown, but the workshop takes great care in restoring them and putting them back into circulation. They are blank slates with a hidden past, ready to be filled with the history of the new wearer. The restored items are co-branded as ‘Renewed Apparel’ and customers are informed about the process they ran through at the workshops. It seeks to revalorize ‘the original creative, financial, material, natural resource, and labor investments that went into making something in the first place’.

→

Gathering common motivations that unite a broad range of practitioners, ‘FASHION FROM THE SHADOWS’ -series aims to map alternative approaches to thinking, creating, presenting and discussing fashion. It provides an overview of recent developments in the discipline in order to integrate them into a new and more inclusive fashion system that encourages discussion. Instead of being suppressed, these alternatives broaden fashion’s spectrum of activities and help to provide a more complete understanding of the spirit of the time which fashion has always sought to reflect.